The Caravan War

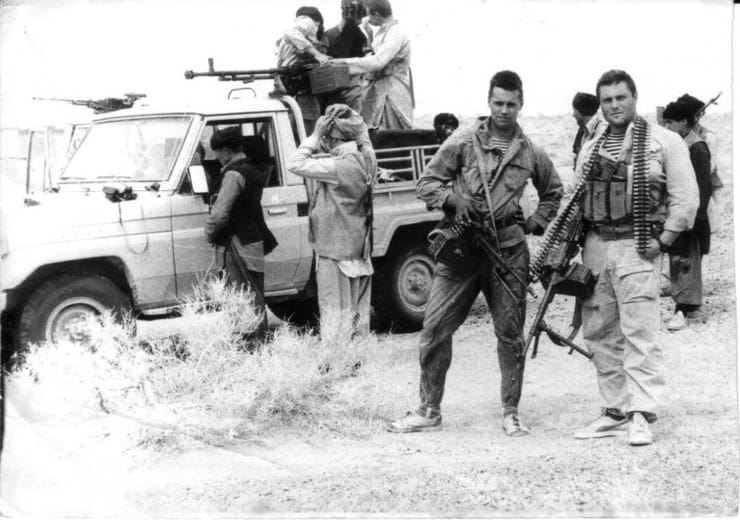

What are the options available when facing an actor in an unconventional warfare environment? To cut off the supply chain and limit long-term operating capabilities, for example. In 1984, the Soviet Union decided to attempt this strategy in its own unconventional manner. The armed forces created brigades of caravan hunters to track down approximately 200 supply routes from Pakistan and Iran into Afghan territory.

Operation Curtain was as much detective work as it was the responsibility of special forces detachments. An estimation of 80,000 troops is needed to close or closely monitor the entire Afghanistan – Pakistan border. On the other hand, 2 brigades held the responsibility of monitoring the border. The caravan hunters faced an unlikely successful scenario, even if logistics and structure provided more support.

In 1984, the Afghan war reached its mid-point mark and the Soviet Union, meanwhile, failed to deter the Mujahideen. The geographic conditions and nature of the war required an increase in support to deter the Caravans. The USSR doubled down on initial approaches. The creation of special forces detachments, or caravan hunters, along the borders marked the beginning of the ‘Caravan War’. Unorganised and semi-autonomous, by 1988 the detachments only managed to stop between 12-15% of caravans.

The structure and method of fighting Caravans

Operation Curtain likely depended on the nature and effectiveness of special forces. Although motorised rifle battalions monitored conventional routes, the supply of caravans required the use of unconventional warfare. The caravan hunters, stemming from GRU special forces, deployed in 2 brigades to prevent the flow of materials through ‘unconventional’ routes.

Despite the significance of the operation and its bureaucracy, the reinforcement of special forces was unorganised and rushed. The 15th and 22nd special brigades managed 4 detachments each, 6 being created, prepared, and deployed between 1984-1985. Simultaneously in 1984-85, reconnaissance units are strengthened within each detachment using MI-8 and MI-24 helicopters. In the end, the expansion and strengthening of the caravan hunters was compressed into a one-year margin including training.

- 15th Brigade: 154th, 177th, 668th and 334th detachments.

- 22nd Brigade: 173rd, 370th, 186th, 411th detachments.

- 459th special forces company in Kabul

Expertise and legend-status ≠ Success

Depending on the experienced detachments affected the reality of Operation Curtain. The first three detachments – 177th, 173rd and 154th – composed the original special forces deployed in Afghanistan, known as the ‘muslim battalions’. All of the personnel was initially intended to belong to an Asian ethnicity to increase the legitimacy in communities in Afghanistan.

Originating from the GRU special forces, the 154th detachment participated in the assault on Amin’s palace. The 177th detachment initially planned to operate in the Xi Xinjiang region in China and was composed of 300 Uyghur personnel. The expertise of the 3 detachments, all formed in 1979 and 1980, did not influence the performance of the rest of the hunters. The majority of caravan hunters remaining lacked the training needed to conduct raids, ambushes and seizures.

Operation Curtain: Low-Quality Training

The advantages of the secret nature of the caravan hunters ended wasted due to poor training. The concept of ‘separate motorised rifle battalions’ replaced the detachments to maintain the clandestine nature. Nevertheless, training in its majority was similar to a common motorised rifle division, with no infiltration, clandestine, or reconnaissance training. According to veteran Valery V. Marchenko, proving capabilities was for show more than action, and detecting caravan hunters was not difficult due to poor performance. For example, the 186th detachment failed to detect a group of surrounding enemies kidnapping a unit scout, or hostages fleeing through man-dug tunnels. In another example, the lack of discipline and preparedness forced caravan hunters to shorten travel distances during raids to avoid fatigue, such as from a helicopter 1Km landing distance to a 200 meter one.

Marchenko states that, at best, only through the rear of a caravan would special forces be able to conduct reconnaissance, collect intelligence and confiscate material. The units intended to fill the vacuum of unconventional warfare lacked the basic abilities of Spetsnaz units. The heads of special intelligence allegedly avoided setting difficult tasks due to the quality of the units. Despite the low quality of the direction and orders, it is likely that the unconventional caravan hunters did not have the knowledge to achieve the strategic purpose of the mission.

The Caravan Hunters or The Caravan cowboys?

The poor training led to a missing component when hunting caravans. The lacking unconventional skills made the definition of caravan hunters literal. Teams of helicopters commonly identified and inspected a caravan. After inspection, the caravan would commonly be torched and caravaneers killed. With the intelligence component completely abandoned, the Spetsnaz hunters meanwhile literally played a cat and mouse game with caravans supplying the mujahideen. It was tactical considerations, and not strategic decisions, that run the hunters on a day-to-day basis. Groups of 10-25 personnel moved to intercept caravans with little objective further than destroying any weapons intended for rebels.

Tactical intelligence or a few exceptions?

Intelligence, or in its place information of low reliability, became the orchestra director of the caravan war. The caravan hunters worked using the 1K18 Sensor that picked up signals of movement. Meanwhile, human sources transmitted intelligence to the detachment regarding caravans and routes. A detachment in the 22nd brigade allegedly controlled a Baloch, who in exchange for intelligence, obtained access to a portion of the intercepted caravans of his choice. Nevertheless, it is likely that the sensors and Baloch informants are exceptions. Intelligence from Kalat, where the GRU intelligence directorate was located, almost never provided accurate information. As an example, the largest caravan seized with more than 200 camels was found by accident, therefore intelligence played little-to-no role.

Bad organisation leading the orchestra

In practice, the special forces detachments enjoyed half-freedom on the front-line to hunt down the caravans. ‘Ekran’, the task force created to oversee the Caravan War, failed to monitor the operation. The task force lacked the logistics to run aerial and reconnaissance operations continuously. Ekran, to a certain extent, was driving the cowboy nature of caravan hunters. Ultimately, Ekran acted like a hedge fund that caravan hunters used to financially and materially support the targeting of caravans.

A poor track record

The poor strategy employed brought occasional successful operations along with a majority of defeats for the caravan hunters. Between 1984 to 1988, 554 detachment members from the 15th special brigade died in attacks and ambushes while hunting caravans. As caravans traveled along routes, mujahideen sometimes escorted the materials and ambushed special forces, mostly unprepared for unconventional scenarios.

Due to the bad organisation of the detachments and a superficial clandestine cover, the hunters also lacked cooperative capabilities. In 1988, during the exit of forces, the 177th detachment in Ghazni mined a field separate from the knowledge of soviet forces. A Soviet vehicle, after insurgents attacked the fleeing forces, ended trapped in the minefield. Ultimately, all of the sappers sent died, along with the commander. In an attack on the GRU directorate in Kalat by insurgents, caravan hunters abandoned a scout who would later die after forgetting to wake him up.