In 2018, more people were displaced in Ethiopia than in any other country in the world. According to the United Nations, by December last year, approximately 2.9 million people were forced to leave their homes, more than in Syria, Yemen, Somalia and Afghanistan combined. Much of the displacement can be attributed to the rise in the ethnic conflict that has engulfed most of the country and was incited following the appointment of Abiy Ahmed as Prime Minister. The conflict and ongoing tensions are probably the greatest threat to his government and its reformist agenda.

A force to great to ignore

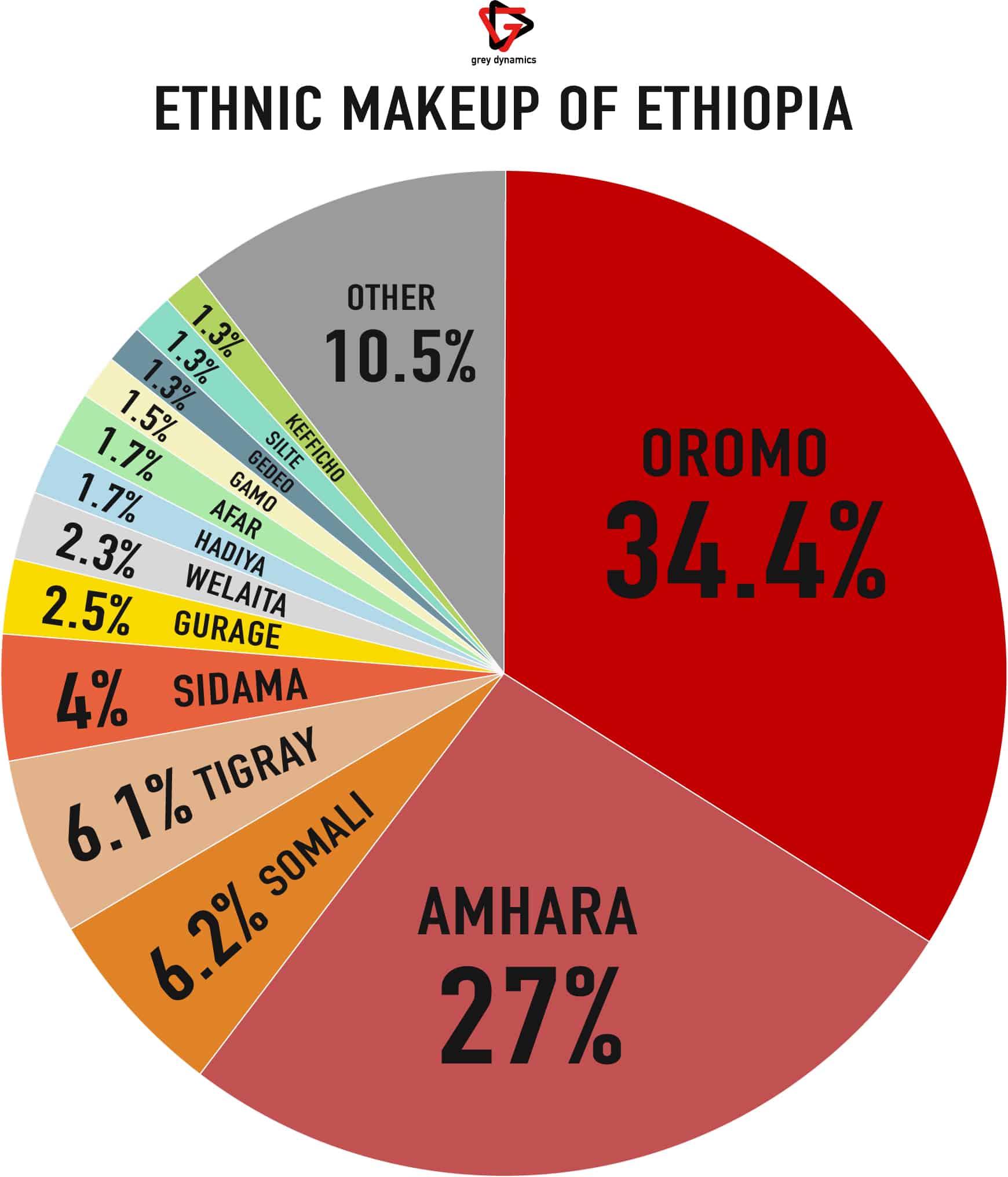

Ethiopia has a population of around 100 million, the second-largest in Africa, and a multi-ethnic federation with more than 80 ethnolinguistic groups. Historical tensions between ethnic groups were previously repressed and handled with a heavy hand by the state.

- OCT 2016 – Government declares state of emergency after months of violent anti-government protests

- FEB 2018 – Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn resigns over continued protests

- APR 2018 – Abiy Ahmed, an ethnic Oromo, is appointed leader of the ruling EPRDF party and named prime minister. He pledges comprehensive political reforms, to mend diplomatic disputes, and pledges reconciliation after decades of a hardline security policy

- MAY – JUN 2018 – Government releases thousands of political prisoners and ends the state of emergency

- JUL 2018 – Ethiopia and Eritrea sign peace deal to end 20-year conflict

- OCT 2018 – The government signs a peace deal that ends the 34-year armed rebellion by the separatist Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF); parliament elects Sahle-Work Zewde as Ethiopia’s first woman president

A country set ablaze

The changing of the political guard last year paved the way for ethnic tensions to boil over. In the Oromiya region, the largest in the country, there are at least four separate conflicts and a border dispute. The conflict between Oromos and other groups, including Gedeos and Somalis, has led to nearly a million people fleeing in 2018 alone.

The Oromo are Ethiopia’s largest ethnic group, roughly a third of the country’s population, and have voiced their complaints of marginalization. Prime Minister Ahmed is the first Oromo leader in Ethiopia’s modern history. His rise to power is widely considered to have awakened Oromo sentiment. In December, the UN was concerned that this conflict could spill over into Kenya.

The conflicts are mostly overgrazing and cultivable land, and resources, such as water. Human rights activist Wario Sora told Al Jazeera that “people have been killed, business premises bombed and torched, houses have also been set ablaze in the fight between Oromo and Somali Garre fighters”. The Guji and Gedeo groups have also clashed in the south with what some observers say is with much greater intensity in than the past.

In the north, conflicts in the North Gondar zone of the Amhara Region have displaced tens of thousands of Amharas. The conflict was ignited after Kemants made demands for self-administration. Furthermore, border tensions are rising between the Amhara and Tigray regions. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) is challenging the federal government after Abiy’s rise to power. The Tigray controlled the country’s ethnic coalition for 27 years prior to 2018.

“You just don’t wake up one day and return half a million people”

In May, the government announced it would ramp up efforts to return the displaced to their homes. This was following the claim by Prime Minister Ahmed in February that over a million people had already been returned. However, humanitarian workers and rights groups think the process is being rushed, even returning people against their will, and believe this puts the people at risk when the underlying causes of the conflicts have not been addressed. One aid worker told the L.A. Times that “you just don’t wake up one day and return half a million people. You need to plan…two years is a viable time frame, not two weeks.”

William Davison, a senior Ethiopia analyst at the International Crisis Group, told Reuters that “there is a risk of further violence that stems from the very ambitious return targets.” The spokesperson from the prime minister’s office told the L.A. Times that, although the return process was compliant with international best practices, cautioned that “hostile” actors wanted to disrupt the process. The spokesperson went on to claim that “there are elements exploiting victims of displacement and conflict for their own agenda”.

A democratic opening

The promise of unprecedented political change in Ethiopia has also left the country susceptible to groups newly asserting their rights, and often in the most violent of ways. This may be unavoidable the country transitions from decades of authoritarian rule. An article by Foreign Policy earlier this year warns of a “double-edged sword” of the empowerment of ethnic groups and placing ethnicity at the centre of politics that could put the country down the same path as the former Yugoslavia.

Awol Allo, a lecturer at Keele University’s School of Law, told Al Jazeera that “what makes this senseless violence even more outrageous is the fact that it is happening at a time when there is such a remarkable level of democratic opening in the country.”

On the first anniversary of his rule in April, Prime Minister Ahmed said“he is only planning to elevate Ethiopia to high standards, awaken the public and lift up a country that is hanging its head. I don’t have any other ill intentions other than that.” With a humanitarian and security crisis on his hands, these are lofty words by the Prime Minister. One only can hope he can answer the call and fulfil his promise.

Image: Tiksa Negeri / Reuters / Houston Public Media (link)